Supporting Food-Insecure Students During Summer

Blogs

Nearly 24% of households with children were food insecure last year, and one in eight children went hungry in 2021. With the discontinuation of many COVID-19-related food assistance policies and recent inflation that has increased food and living costs, the number of children and their families facing food insecurity is expected to be even higher in 2023.

It’s disheartening to know that many students face the harsh reality of food insecurity, which can be exacerbated by summer break. The unsettling truth is that hunger affects students in ways that extend beyond their empty stomachs. As educators, administrators, and community members, it’s essential to delve into the underlying reasons behind this issue and explore strategies to combat summer food insecurity, ensuring access to nutritious meals during summer break.

What is Food Insecurity?

Food insecurity is when a person or household does not have consistent access to safe, nutritious, and culturally appropriate foods to live a healthy and active life. Things like income, living costs, medical conditions, food allergies and restrictions, the number of people in the household (and their ages), and even where someone lives can impact whether a person has access to enough safe and healthy foods.

Why May a Student Be Food Insecure?

Food insecurity in students can arise from a multitude of factors, encompassing both individual and systemic challenges. Understanding these reasons is crucial for addressing the issue effectively. Here are some key factors that contribute to student food insecurity:

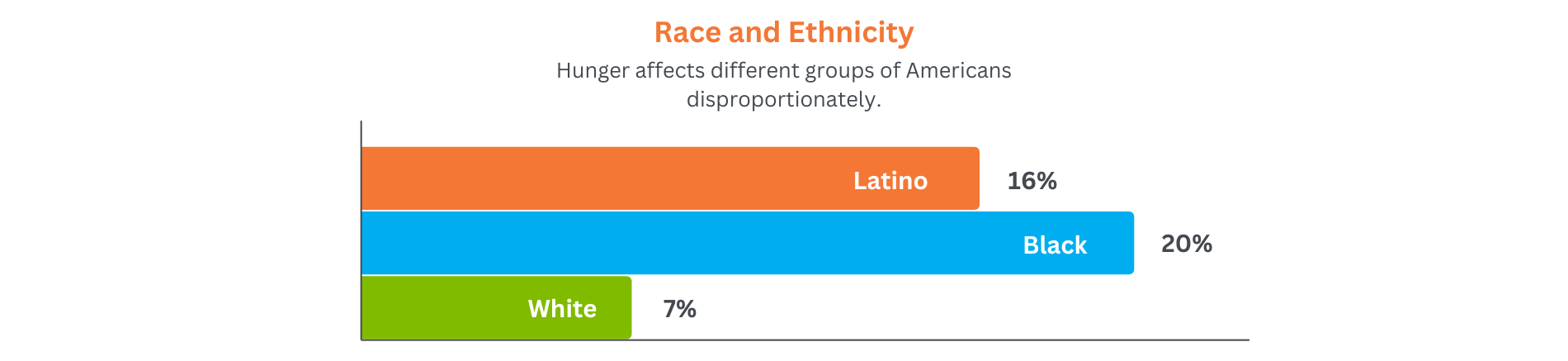

- Marginalized Communities: Children and adolescents who identify as Black or Latinx, live in a single-parent household, and/or live in a rural neighborhood have the highest rates of food insecurity due to unique vulnerabilities and challenges related to structural and systemic inequalities. They may be low-income, live in a food desert (an area that does not have a grocery store or supermarket that sells fresh food), or experience neglect—all barriers to food security for kids.

- Hidden Food Insecurity: Many students may face hidden food insecurity, meaning they do not qualify for food assistance such as free or reduced-price school meals. The truth is that a large chunk of households who struggle to put food on the table, especially nutritious foods, make just over the income threshold required for food assistance like the National School Lunch Program and the Supplemental Food Assistance Program (formally known as food stamps).

- High Cost of Living: After all the bills are paid, which sometimes include medical bills, childcare, or unexpected costs, there simply is not enough money left for food. This is why food insecurity is associated with poor-quality diets comprised of less-expensive processed foods. Children whose families are food insecure may not be able to afford or access healthy foods, or they may not have enough food to eat in general (known as hunger).

- Resident Status: Immigrant households whose members are undocumented are also not eligible for household food assistance. However, all students despite their residence status can participate in the National School Lunch Program. It is important that schools make this known to immigrant families so students can utilize the program without fear.

What Are the Risks for Food Insecurity in Students?

Food insecurity among children and adolescents can have far-reaching consequences for their overall well-being and development. Here are some of the risks associated with food insecurity:

- Impaired Academic Performance: The impact of food insecurity on student performance can be far reaching. Food insecurity among children and adolescents can impair concentration, memory, emotions, and behavior. If you’ve ever tried to focus and work productively with hunger pains, you know how difficult it is.

- Social Isolation and Stigmatization: Food-insecure students often feel embarrassed and face stigma from their peers regarding their status. This can keep students from utilizing school assistance programs like the school backpack program, school food pantries, and even the free or reduced-price lunch program.

- Long-term Consequences: Food insecurity during childhood and adolescence not only has direct effects on school performance and well-being, but it also puts students at risk for future, often long-term, consequences. Food insecurity can negatively impact growth and development, including causing cognitive delays and poor immune response. It is associated with nutrient deficiencies and overnutrition, obesity, increased risk of infections and chronic diseases, and mental health disorders.

- Risky Behaviors: Some teens may adopt risky behaviors to cope with food insecurity such as stealing, having relationships with older individuals, or selling things illegally. These behaviors may further impair school performance, lead to legal troubles, and ultimately prevent potential job opportunities (as well as chances for higher education) that require good academic and behavioral track records.

- Emotional and Behavioral Challenges: You may have heard or used the term “hangry”—a combination of the words “hungry” and “angry”– to represent the common bad mood one can experience as the result of feeling hungry. Along with mood swings, food insecurity can cause emotional distress, anxiety, and depression among children and adolescents. The constant worry and uncertainty about where their next meal will come from can lead to increased stress levels and behavioral problems.

When the impact of food insecurity on student performance leads to poor academic results and behavior, it affects a student’s future. Not achieving good grades can hinder students from future educational opportunities such as college or vocational school.

Signs of Food Insecurity and Hunger Among Students

Administrators and teachers can look out for signs of food insecurity and hunger among students, especially those who may not be on food assistance. Some clues include:

- negative behavior and/or bullying

- poor concentration and/or memory

- emotional indicators such as sadness

- reservation or anger

- speaking about hunger or asking for food

- hoarding food

- sudden weight changes

If you notice a student is showing signs of food insecurity, avoid calling attention to this in front of their peers. Instead, have the guidance counselor meet with the student about the concerns and strategize a plan to help privately.

Summer Challenges for Food-Insecure Students and Families

Success for students, now and later, is intertwined with access to enough nutritious foods. Many youths and their families rely on school meals to mitigate food insecurity. During summer vacation, students may not have regular access to meals like breakfast and lunch as they would when school is in session.

Furthermore, households must buy and provide more food for children to supplement what they are not getting from school, and some may also have to pay for childcare. These are increased costs that can be a large burden for low-income families, especially those with single parents.

Even when children and teens have food at home, they may not know how to prepare food for themselves. This can further motivate poor dietary choices such as the reliance on highly processed foods that can be microwaved or snack foods that do not require cooking or preparation. It can also keep kids from eating regularly.

Summer Meal Programs for Food-Insecure Students

The USDA funds summer meal programs for food-insecure students, ensuring access to nutritious meals during summer break. The federal Summer Food Service Program provides at least one meal per day for children up to the age of 18. Any child or teen can participate–they do not have to pre-qualify, provide proof of income, or be legal residents. This makes the program more inclusive and eliminates the stigma often associated with income-based food assistance.

The programs are state managed. This means their availability and locations vary by state and community. Most summer meal sites are hosted at community centers, churches, parks, and schools.

There are easy ways to find a nearby summer meal site. You can use the USDA Summer Meals Site Finder, Text “FOOD” or “COMIDA” to 304-304, or call 1-866-348-6479. School administrators can share these tools as well as use them to help inform students and their families of summer meal programs in their communities.

What You Can Do if There Is Not a Summer Meal Program Near You

If there is not a summer meal site for children in your area, there are several resources you can refer students and their families to.

- Local Food Pantries Or Kitchens: The Find Your Local Food Bank search network from Feeding America will find the nearest food bank to the zip code provided. From there, you can click on “find food” to find local pantries associated with the Feeding America food bank.

- USDA National Hunger Hotline: Individuals can also call 211 or the USDA National Hunger Hotline at 1-866-348-6479 (also available for Spanish speakers at 1-877-842-6273) to find immediate assistance.

- Food Assistance Networks: Each state and county/city will have its own food assistance network. There may be some local pantries and kitchens that permit children and teens without an adult. In addition, there may be mobile pantries or delivery options that help get food to households with children that otherwise are not able to get to a pantry or kitchen due to work, disability, or lack of transportation.

Schools should familiarize themselves with local and federal food assistance opportunities to ensure they’re supporting food-insecure students during summer. Creating a food assistance guide for students and their households can help ensure families are knowledgeable of the resources available and go a long way in terms of food security for kids.

Schools can also apply to become summer meal sites. To learn more about operating a summer meal site and how to apply, visit the USDA’s How to Become a Sponsor webpage.

Meet the Author

Mecca is a PhD candidate in the Department of Anthropology at Indiana University. She received her M.A. in applied anthropology in 2018 from the University of South Florida. Her research focuses on the impacts of sociopolitical factors and food systems on food security, nutrition, growth and development, and health. She has published various peer-reviewed articles on food insecurity, including among children and adolescents, and is dedicated to applied work including science communication, advocacy, and community-based initiatives. She is currently working on community-led youth food security projects in Indianapolis and Costa Rica.

Are you ready to make your school safer?

You focus on education—we’ll handle accident and compliance management. Learn more about our educator and staff compliance training today!

Learn More